The Escort Cosworth WRC is a true fast Ford unicorn. Built in very limited numbers, it was simply the highest-specification and most technologically advanced of all the Cosworth rally cars. Graham Robson tells the full story of this legendary motorsport machine.

Feature from Fast Ford magazine. Words: Graham Robson. Photos: Ford Photographic Archives, Ade Brannan, & Getty Images

This story began in 1996, when Ford Motorsport’s Boreham operation was in transition. The Escort RS Cosworth was past its peak, chief design engineer John Wheeler had been promoted to run Ford’s Aston Martin DB7 technical operation in the Midlands, and there was turmoil at the top of the sport.

The original World Rally Car regulations were due to take effect in 1997, but Ford Motorsport needed a new model. There wasn’t a suitable car to meet the new rules, and the outgoing Escort RS Cosworth – built to Group A regs – would no longer be eligible.

From a technical point of view, the new rules were easy enough to meet. But would Ford have a suitable base car available by 1 January 1997?

This was the dilemma. Although only 20 new WRC machines had to be built in one season (none of them for use as road cars), they would have to be based on models of which at least 25,000 examples were being built in a year.

That was the bad news. The good news was that homologation rules had effectively been binned; no longer did manufacturers need to build costly (often loss-making) special editions of their road cars just in order to make them eligible for racing.

Almost every other modification to the basic specification of the mass-produced road car was allowed; conversion from front-wheel drive to four-wheel drive was authorised, as was turbocharging otherwise naturally-aspirated engines, and a complete redesign of suspension geometry was allowed.

In fact, the only thing WRC cars had in common with the road cars (apart from the model name) was that the engine had to be no more than 2.0-litres in capacity.

Group A competition (in which Ford’s Escort RS Cosworth was still a leading contender) was about to be ruled out, and the new World Rally Car regulations were to be applied from 1 January 1997, but with certain exceptions.

It was the exceptions, and the opportunities they presented, that caught Ford’s eye.

New rules, same car

One big change from the past was that World Rally Cars would never be allowed to be reshelled. If a motorsport shell had to be written off – specifically, if the integral roll cage was rendered useless – so did the identity of that car. Suddenly, as far as enthusiasts were concerned, this made number-plate-spotting worth doing again.

Even before they started the job, Boreham’s engineers – then led by Philip Dunabin – soon realised that a World Rally Car (WRC) could eventually become very specialised. The bad news was that it would immediately make the existing Escort RS Cosworth obsolete.

In 1996, Ford’s biggest problem was that, according to the new regulations, for 1997, WRCs had to be based on a current 25,000 units-per-year model. There was no way the old Escort RS Cosworth could satisfy this, and it was soon to go out of production anyway. But there was no other obvious Ford model that qualified; the Fiesta was too small, and the Escort’s replacement (the Focus) would not appear until 1998 – meaning a WRC version could not be readied before 1999.

It was time for the FIA’s bluff to be called, and as one of the few manufacturers currently dedicated to a full world rally programme, Ford decided to do just that. Ford’s bigwigs told the FIA that building an all-new WRC was currently out of the question, but offered a short-term solution that would need the consent of rival manufacturers to make it feasible.

If the FIA would let Ford’s first-generation WRC be based on the old Escort RS Cosworth, they stated, then works-backed Fords could be on the starting line for the Monte Carlo Rally in January 1997. And if not, Ford would have to withdraw.

Time to lose

Unsurprisingly, the FIA soon agreed to the proposal. After which, the rush to get a competitive Escort WRC designed, developed and ready began at high speed. Boreham did all the design and original development work, though (as we now know) Malcolm Wilson’s M-Sport team would eventually get the contract to run the team cars (and built them all) from the start of 1997.

Concept engineering work began in June 1996 and the first prototype ran on 13 October. The media launch followed on 3 November, and the homologation inspection of the 20 kits of parts was completed on 19 December 2020 – just a few weeks before the first event.

There was such a rush that Motorsport at Boreham only built two prototype test cars: N704 FAR (tarmac-spec) and M513 WJN (gravel-spec). Both were originally Group A Escort RS Cosworth rally cars that were converted to WRC-spec.

That was a super-rapid programme by any standards; the Escort WRC had gone from being a feasible idea to race-ready homologation in six months.

Spot the difference: Escort WRC vs Escort RS Cosworth

In evolving the Escort WRC from the Escort RS Cosworth, Motorsport made several improvements, but the main upgrades are highlighted below.

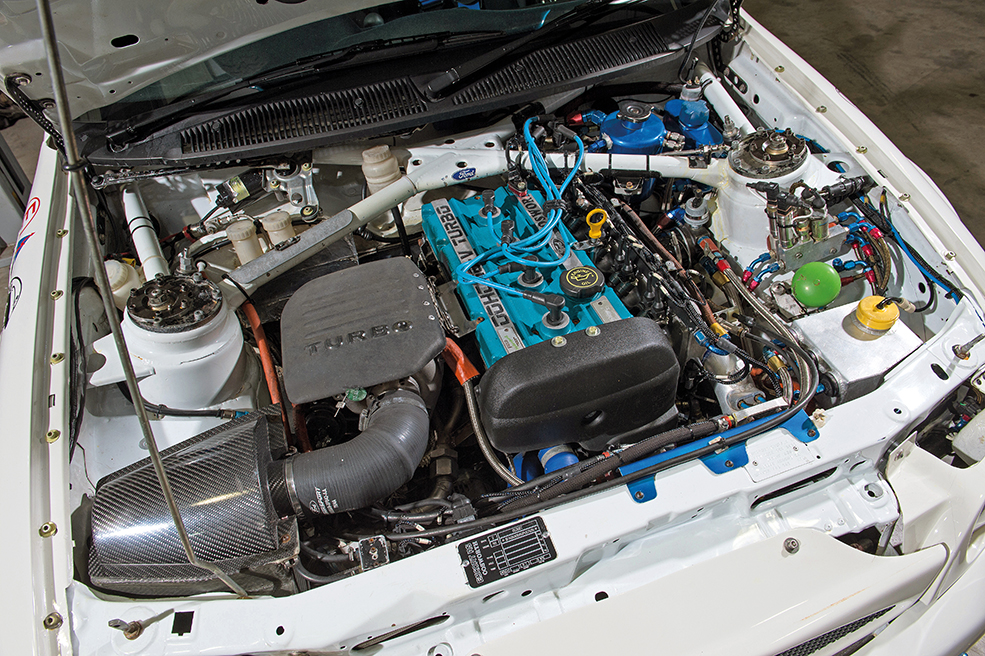

A new YB engine: a new, smaller IHI turbocharger (to suit a 34mm restrictor), different exhaust manifold, and fuel injection changes (with eight instead of four active injectors). This delivered 310bhp at 5500rpm, with a very solid torque curve.

Cooling: better airflow through larger front apertures, with repositioned and more efficient intercooler and water radiators.

Rear suspension: lighter and stronger tubular subframe, with a new MacPherson strut/links system, with a geometry rather like that of the Mondeo.

Aerodynamics: new front bumper profile to suit the revised radiator and intercooler relocation. Smaller, reshaped rear aerofoil to generate more downforce with less drag.

Layout: idealised layout, with an 80-litre fuel tank, spare wheel, and 40-litre water reservoir (water to be available for cooling sprays) all positioned in the rear compartment. The aerodynamic tests were carried out in the Ford wind tunnel at Merkenich in Germany, resulting in improved downforce. In any case, the new rear aerofoil had been needed to satisfy WRC regulations, as the existing RS Cosworth style was too large. The engine water radiator was 33 per cent larger than before, and the turbo intercooler 50 per cent larger (it was also cooled by water spray from the reservoir). The intercooler was repositioned, now being ahead, rather than on top of, that radiator.

Escort Cosworth WRC: Instant Hit

For the very first time, the works cars would be run by an outside agency. At the end of 1996, Malcolm Wilson’s M-Sport team took over for Ford. Although Motorsport at Boreham takes all the credit for the design and development of the Escort WRC, and for organising the hurried manufacture of the first 20 sets of components, it was Malcolm Wilson’s team that would always run the cars.

The story of how M-Sport managed to get two cars ready for the Monte Carlo Rally in 1997, where Carlos Sainz finished second overall, and where Carlos and Juha Kankkunen took a 1-2 finish in the Acropolis later that spring, tells us a lot about the merits of this rushed programme.

In just two years, far more Escort WRCs were built than many observers were prepared to believe at the time, but the boxout on the previous page confirms this.

Forty different works or works-blessed Escort WRC models were completed between 1996 and 1998. In addition, several other Escort WRC models were created by private owners in later years, for their own use, by updating Group A Escort RS Cosworths with kits provided by M-Sport.

To complicate matters further, the Escort WRC replica that featured on the Ford press fleet was a lookalike with a full-spec engine and aerodynamic kit, but lacking all the items of the WRC kit (for instance, it used a five-speed gearbox).

Except for chassis number 038 (R6 FMC) – which was driven by Petter Solberg on the Swedish Rally of 1999 – all the works cars were sold off or retired at the end of the 1998 season. For 1999, Ford and M-Sport had invested heavily in the first of its ground-up WRC machines, the Focus WRC. But that’s a different story for another day…

How many Escort Cosworth WRC cars were built?

As far as is known, this is a complete listing of every official Escort WRC that was built either at Boreham or by M-Sport. It is worth noting that several clones were built by private teams and individuals in the years that followed.

| Year | Built By | Registration | Notes |

| 1996 | Boreham | N704 FAR | Tarmac test car. Ex-1996 Group A car. |

| 1996 | Boreham | M513 WJN | Gravel test car. Ex-1996 Group A car. |

| 1997 | M-Sport | P7 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | P6 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | P11 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | M10 MWM | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | M40 FMC (later P6 FMC) | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | Not completed | / | |

| 1997 | Mike Little Preparations | P194 FAO | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | RED | P10 RED | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1997 | M-Sport | P8 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | P9 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | unknown | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | Boreham | R475 KVX | |

| 1997 | Mike Little Preparations | M743 YWC | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | Boreham | R963 DHK | |

| 1997 | RED | unknown | |

| 1997 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1997 | Finland | unknown | |

| 1997 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1997 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1997 | Greece | unknown | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | unknown | |

| 1997 | Mike Little Preparations | unknown | Ex-Group A car |

| 1997 | Boreham | R771 GTW | |

| 1997 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1998 | M-Sport | R3 FMC | Works Valvoline car |

| 1998 | M-Sport | R4 FMC | Works Valvoline car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | R2 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1997 | M-Sport | R1 FMC | Works Repsol car |

| 1998 | Jolly Club | R9 FMC | |

| 1998 | Jolly Club | R10 FMC | |

| 1998 | Boreham/MLP | unknown | |

| 1998 | M-Sport | unknown | |

| 1998 | Boreham/MLP | unknown | |

| 1998 | M-Sport | R5 FMC | Works Valvoline car |

| 1998 | M-Sport | R6 FMC | Works Valvoline car |

| 1998 | Boreham | unknown | |

| 1998 | M-Sport | S13 FMC | Works Valvoline car |

| 1998 | Not completed | / | |

| 1998 | Boreham | unknown |